Stitched Together: Freedom Colony Families Along the Cibolo

In 1847 Joseph and Mary Polley loaded up all their worldly possessions into carts, and leaving the rather established community in Brazoria, headed some 200 miles to the Texas frontier on the banks of the Cibolo Creek in Wilson County. They would spend the next twenty years establishing their plantation, creating a flourishing cattle business, raising and educating their children, creating a community for their family, servants, visitors, and slaves, and building and furnishing a beautiful stone house that has endured for over 175 years.

|

| Polley Mansion, Whitehall. Courtesy of Robin Muschalek |

| |||

| Piano owned the Polley family, now in the possession of a family member |

We know many details about the J. H. Polley’s family gleaned from letters, receipts, family manuscripts, deeds, legal documents, and newspaper articles. The Slave Schedules record the gender, age, and color of each of the men, women, and children enslaved by Polley. Although some of their names and a few facts about them can be gleaned from manuscripts, letters, newspaper articles, and books written by Polley family members, very little is known about the enslaved people who built the house, grew the crops, fed and clothed the Polley family, wrangled the cattle, raised and cared for their own families, and helped to make the Polley Mansion, Whitehall, a successful enterprise.

|

| Slave Kitchen at the Polley Whitehall Mansion, Sutherland Springs, Texas |

The story of the Polley plantation was not unique. Between 1840 and 1860 thirty-seven other plantations with at least five or more slaves had been established in the Cibolo Valley,[7] and others along the Guadalupe River to the east and the San Antonio River to the west. About 1000 enslaved people lived in Wilson County and 1800 in Guadalupe County in 1860. Settlers from Austin’s Colony along the Texas coast, like the Polleys, and others from the deep South came to establish cotton plantations along the Cibolo Creek. They brought their enslaved people with them to work the land. They eventually learned that that part of Texas was a little drier than the Texas coast or the deep South, and many gave up on cotton production and opted for the cattle business instead. Some of their enslaved people became cowboys instead of farmers.

| ||

| Krazy Quilt made by Texana Rosser (1856-1911) |

My grandmother, my husband’s grandmother, and great-grandmother, and one of my aunts were quilters, taking bits of fabric and stitching together sometimes works of art and sometimes practical coverings to keep their families warm and comfortable. Sometimes they worked alone; sometimes they worked together. My Aunt Jeanettie pieced her quilts on a treadle sewing machine on her front porch in the foothills of the Ozarks. She quilted them in the winter in front of her wood-burning stove in her cabin. They smelled like smoke. My grandmother carefully cut out designs of Dutch girls, nine-patches, and sunflowers, and set them in carefully planned blocks, using leftover scraps from my dresses and those of the other children and grandchildren. My husband’s grandmother joined with other neighbors in her community to quilt in the room at the back of her house that she had specially built as a quilting room. She sewed every block and stitched every quilt by hand. Using a machine was simply not allowed. I tried to learn from her, but I could never get my stitches small enough to suit her. One of my prized possessions is a cross-stitch quilt she worked on while she sat at the bedside of her husband, tending him during his last days. I have a couple of crazy quilt pieces that were made by my husband’s great-grandmother, Tex Anna Rosser. Crazy quilts were all the craze in the Victorian era, made to show off bits of fancy fabrics, satins, and velvets, and the quilter’s expertise at doing fancy stitches. The stitching was for adornment, not practicality.

|

| Late 19th -century linsey make-do quilt by "Mother Ferguson," an African-American Texan |

At the same time Tex Anna Rosser was plying her fancy skills on the crazy quilts, some of her neighbors were stitching together quilts that were a bit more practical. Those quilts were made from old worn-out clothes or discarded feed sacks. Their stitches were made hurriedly at night by the light of a candle or a coal-oil lamp after a long, hard day of work in the fields or in the house. They were made to keep their families warm and to add a bit of comfort to their lives. They were “make-do” quilts. Not many examples survive; they just eventually wore out.

|

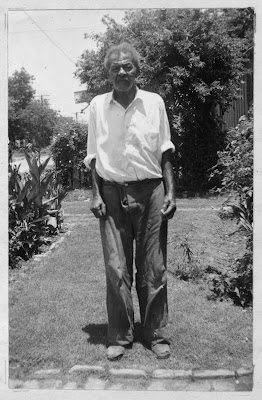

Albert Todd (1855-1940) lived in Wilson County from 1860-1910. |

This book is about what happened to those people who had lived in slavery in plantations along the Cibolo Creek in Wilson and Guadalupe Counties and became free men and women and children on June 19, 1865. It is about their tenacity, ingenuity, successes, and failures. It is about how their former enslavers helped or hindered their success. It is about how they educated their children, sought hope and comfort in their houses of worship, and banded together to help each other make a living out of the land. It is about how the political machinery of Wilson County aided their transition to freedom and how it sought to eradicate them from the face of the earth. It is about how some of them cut off all bonds with the Cibolo, some of them kept connections with the old home places, and some of their descendants stayed even until today. It is not a story that is clear-cut or easily understood or even comfortable to hear. But it is part of our story. It is a story of intense, inhumane suffering and extraordinary leadership and resilience. It is a story of sorrow, sickness, and death, and health, joy, and longevity. It is not a story of the whole fabric of their lives. It is just scraps, gleaned from Slave Schedules, Census Records, Freedman’s Bureau reports, County Clerk public records, Probate records, Public School records, newspaper articles, diaries, family stories, and a few books. All of those are stitched together to tell a story of the freedom colony families along the Cibolo.

[1] In the 1930s the family loaned the seven boxes of family papers to the University of Texas to be photostatically copied. Those archives remain at the Briscoe Center, although the location of the original papers is no longer known.

[3] Receipt from the Forbes and McGee Shipping Company, 25 July 1859, Polley Family Papers, 1824-1976 (bulk 1855-1875), MSS 7633, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

[4] Richard B. McCaslin, Sutherland Springs, Texas: Saratoga on the Cibolo, 1st Edition (Denton: University of North Texas Press, 2017), 16.

[5]United

States Bureau of the Census, Seventh Census, 1850, Texas, Schedule Two, Slave

Population: Guadalupe County.

[6] United States Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census, 1860, Texas, Schedule Two, Slave Population: Guadalupe County.

[7] “The End of the Road for the Southern Plantation,” Lost Texas Roads, accessed August 16, 2023, https://losttexasroads.com/the-end-of-the-road-for-the-southern-plantation/.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Comments

Post a Comment